[A continuation of part one.]

Cohen, Guskey, Schimmer, Wormeli

Many teachers worship at the church of the arithmetic mean.

In Fair Isn’t Always Equal (2006), Rick Wormeli writes:

… it’s easier to defend a grade to students and their parents when the numbers add up to what we proclaim. It’s when we seriously reflect on student mastery and make a professional decision that some teachers get nervous, doubt themselves, and worry about rationalizing a grade. These reflections are made against clear criteria, however, and they are based on our professional expertise, so they are often more accurate. Sterling Middle School assistant principal Tom Pollack agrees. He comments, “If teachers are just mathematically averaging grades, we’re in bad shape.” (p. 153)

The best case I’ve been able to make for why the practice of averaging is so fraught is given by Thomas Guskey in On Your Mark (2014):

Can you imagine, for example, the karate teacher suggesting that a student who starts with a white belt but then progresses to achieve a black belt actually deserves a gray belt? (p. 89)

Tom Schimmer hammered this point home in a December 2013 webinar called “Accurate Grading with a Standards-based Mindset”:

Adults are rarely mean averaged and certainly, it is irrelevant to an adult that they used to not know how to do something. Yet for a student, these two factors are dominant in their school experience.

In his article published in the April 2016 issue of “Educational Leadership,” Guskey echoes Wormeli’s point that defensibility and the perception of objectivity are highly prized among many teachers:

In teachers’ minds, these dispassionate mathematical calculations make grades fairer and more objective. Explaining grades to students, parents, or school leaders involves simply “doing the math.” Doubting their own professional judgment, teachers often believe that grades calculated from statistical algorithms are more accurate and more reliable.

In this blog post, David B. Cohen makes the case for reforms many folks in the TTOG community have been pushing for for some time:

We need to relinquish our preconceptions about the meanings of specific numbers and percents. Giving up the idea of points altogether would help; points are a convenient fiction, as long as you don’t think too hard about what they supposedly represent.

Cohen recommends ditching the 100-point system:

Why do we need 100 points then? That’s a level of definition that has no meaning. It would be like having a weather report stating today’s high temperature was 58.3 degrees, or including cents in conversations about rents or mortgage payments.

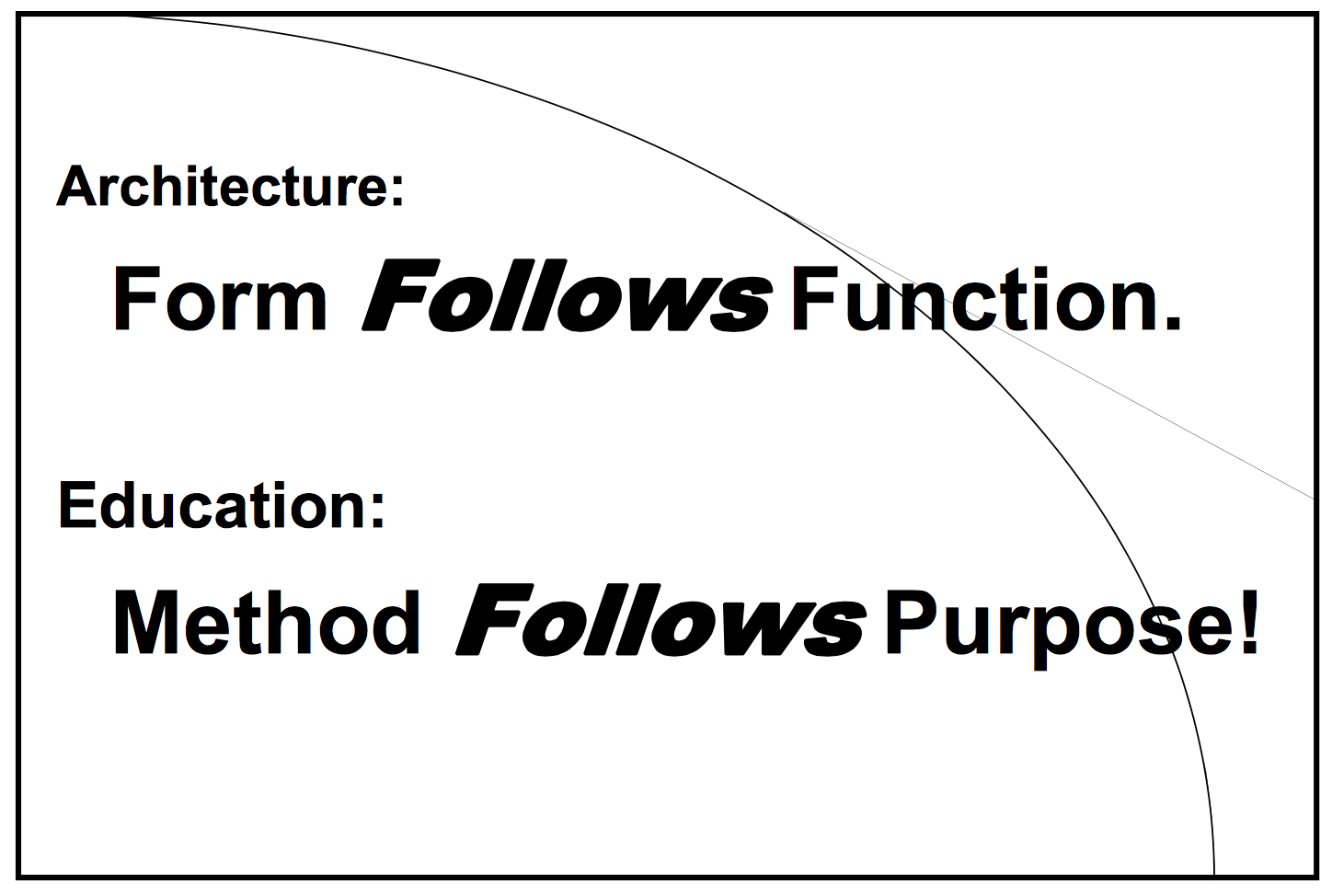

All of these points and reforms encounter institutional resistance, however, because of how much they ask teachers to make major shifts in their practice.

For me, though, it’s worth it. I was so glad to see this article by Alex Carpenter and Alberto Oros in the August 2016 edition of “Educational Leadership,” which made the connection explicit between grading practices and enacting a social justice pedagogy. The authors implore us to “take a moment, right now, to think about how we can modify our gradebooks in the name of justice.”

I’ll reiterate my questions from a year ago, because they are still very fresh on my mind.

A couple questions on my mind

- What practices do you, your department, and/or your institution have in place to facilitate difficult conversations about grading, reporting, and assessment?

- To what extent would it be a useful exercise for each department within a school to produce its own purpose statement for grading? (“The purpose of grades within the ___ department at ____ School is …”)